from the creative-thinking... dept

Law professor Doug Lichtman has a monthly podcast (on an annoyingly flash-only website) called the Intellectual Property Colloquium. A few months back, we discussed the episode that looked at

file sharing damages. I must admit that I tend to disagree with a significant percentage of Lichtman's conclusions on intellectual property, but unlike many copyright maximalists, I tend to believe he's much more intellectually honest on these issues. His positions don't seem to come from a "more is absolutely better because it makes me/my clients more money" position, but he honestly tends to believe that greater copyright leads to a greater net outcome, and tends to argue reasonably about it -- though, I believe some of that reasoning, and the assumptions that underpin it are faulty.

In the latest podcast, Lichtman and three guests

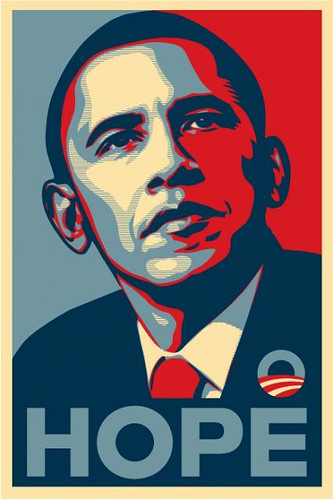

discuss "fair use" with most of the focus being on the

Shepard Fairey case. Lichtman talks with one of Fairey's lawyers (Mark Lemley), a lawyer for the AP (Dale Cendali) and finally the General Counsel of the NY Times, Ken Richieri. It won't surprise many, I'm sure to say, that I strongly agreed with the points Lemley made, in explaining (a) how Fairey's use is almost certainly fair use. But the debate between Lemley and Lichtman is still quite worthwhile.

The key point that Lichtman keeps jumping back to is an interesting attempt to justify blocking fair use on what (at first glance)

appears to be free market principles. That is, Lichtman states, repeatedly, that because Fairey

could have licensed an image of Obama prior to making his artwork, there shouldn't be fair use. His argument is that this is as free market approach, and that fair use might not even need to be considered. To Lichtman, if there is a "functioning" market that can be made, there's no fair use. At a first pass, this may sound quite appealing to free marketer/libertarian types. But it's wrong. That's because what he's talking about is not a

true free market at all. It's an

artificial market, based entirely on a gov't backed artificial scarcity. It's a market built on a monopoly, which is no free market at all.

It also seems to go against the very intent of copyright itself, in that it suggests that as long as there's a "reasonable" tollbooth that can be placed on things, there shouldn't be fair use. But if that tollbooth is actually creating friction and decreasing, limiting or hindering creative output, then it can and should be seen not as "promoting the progress," but the exact opposite. Lemley does a decent job on the spot to warn against the frictions caused by such a "permission" culture, in that it's quite unreasonable in many cases to have to get permission, but Lichtman dismisses this as a minor issue, or really one that can be worked out separately. To me, that suggests a rather distinctly poor assumption about creativity and creative culture these days. Requiring ad hoc permission on any potential use would create massive chilling effects on all sorts of creativity. Lichtman also suggests that a third party intermediary (perhaps YouTube) could serve as a clearinghouse for such rights, but that too creates all sorts of problems.

Overall though, this highlights the problem I have with those who continue to support strong copyrights under a "free market" perspective. A true free market for a good with infinite supply will price that good at zero. But copyright distorts that market to limit that possibilities. It's as if some believe that

any market represents a free market, even if that market is massively inefficient. Back in the days of the sugar monopolies, there was "a market" for sugar, but it was not a fair market price, because of the gov't backed monopoly. Or, to make the point clearer, today there is no "market" for air, despite the fact that it's quite valuable to all of us mammals who like to breathe. We could, in theory, create a gov't backed market for air, recognizing its value, and forcing people to pay to breathe, but most people inherently recognize how inefficient and

wasteful that would be. Yet, content has the same fundamental (effectively) limitless supply as air (if anything, air is more limited). And yet, some think it needs a similar artificial and inefficient market.

As for the rest of the podcast, Cendali's defense of the AP's position was an incredible stretch (and, it was disappointing that Lichtman softballed his responses to her, pretending to "channel" what Lemley might say). Her defense was effectively: "The AP relies on licensing to survive. We need to survive. If what Shepard Fairey did was fair use, then it would destroy the AP, thus it can't be fair use." That's wrong on a variety of levels, and Lichtman barely touched on any of them. The purpose of copyright isn't to protect the business model of a single company. I could create a company that is harmed by fair use of my works, but that doesn't mean they're not fair use. Cendali also induced a guffaw from me in response to Lichtman's question about why the AP didn't notice the fact that its image was being used. Her response was that since the AP has so many images, it would be impossible to track them all and see if they're being used. Indeed, but no one was asking that. What Lichtman asked (and failed to follow up on) was why the AP didn't notice that this image -- which was being used

everywhere -- was based on an AP image. No one expected the AP to track all its images, but you would think with such an iconic image getting so much coverage, that the AP would notice.

Cendali, keeps trying to suggest that the Mannie Garcia photo was something special, but fails to explain (even Lichtman pushes back somewhat, and Cendali answers a

different question) what parts of the photo are actually protectable under copyright. She basically just says that because Garcia was a professional photographer, that the work is clearly covered by copyright. That's not how copyright works, though. She also keeps saying that because Fairey picked

this particular photo it proves that the photo had something special. But, if he'd picked a totally different photo, she'd say the same thing. The simple fact is that Fairey could only pick one photo to make this picture, and this is the one he chose:

"He could have selected any one of probably hundreds if not thousands of photographs, But he selected this particular photograph, and he selected it for a reason, as he's already stated in various interviews. He was looking for a particular photograph that presented Obama in a particular way, in a hopeful way, in a way looking forward to the future... This wasn't just any random photograph... He was looking for a particular photo... and for him to now minimize that is not fair."

No, what's

not fair is claiming that

any of that is the AP's to own. None of it. Not a single part of it was. All of that -- the hope, the way he was looking, was simply there. What made him choose it was the look on Obama's face -- which is not Garcia's creative output, and thus cannot be covered by copyright. In fact, the most frustrating thing of all is that Cendali repeatedly claims that Fairey was

ripping off Garcia (and the AP), but misses the obvious problem with that argument: which is that if her argument is correct, then the AP and Garcia also

ripped off Obama, since it was

his creativity in looking the way he did and making the facial expression he did. Once again, such externalities are apparently only acceptable when the AP benefits. But, Cendali seems to ignore that, and Lichtman lets her get off, noting that he basically agrees with her.

The final guest was actually a pleasant surprise. Richieri notes that he's not a

copyright lawyer, but a newspaper lawyer, and thus doesn't approach things from an "ownership" perspective, but a "fairness" perspective, and notes the importance of fair use in the news business. He doesn't add too much new to the conversation, but it is refreshing to hear someone who, unlike the AP, seems to recognize that trying to own every last word/phrase/headline doesn't really make much sense.

Overall, the podcast is worth listening to, but the Cendali section may involve a bit of headbanging for it being so blatantly mistaken on the very basics of copyright law.

Filed Under: copyright, dale cendali, doug lichtman, fair use, ken richieri, mannie garcia, mark lemley, shepard fairey

Companies: associated press, ny times