Will John Sununu And Harold Ford Jr. Agree To Pay Netflix's Broadband Bill Next Month?

from the simple-request dept

Not this again. I thought that we were well past lobbyists publishing op-ed pieces in which they flat out lied about how broadband pricing works. Almost exactly five years ago, we called out (then) telecom lobbyist Mike McCurry (a former Clinton press secretary) for his bizarre and ridiculous claim that Google got its bandwidth for free. We asked, if that was the case, if McCurry would agree to pay Google's bandwidth bill. McCurry never responded, though the astroturf group he ran at the time was clearly reading, since they took other comments of mine totally out of context at a later date.It looks like we're in for a repeat with some other ex-DC folks-turned-sell-out lobbyists. This time, it's former Senator John Sununu and former Rep. Harold Ford Jr., shilling for "Broadband for America," claiming that Netflix gets its bandwidth for free. There are so many things wrong with this particular op-ed piece, which is so dishonest that the Mercury News should publish a full retraction and apology. But, for now I'll just make the same deal that I offered to McCurry five years ago:

If John Sununu and Harold Ford Jr. really believe that Netflix is getting a "free ride" with its bandwidth and this is somehow socially irresponsible and unfair, will they agree to pay Netflix's broadband bills for the rest of this year?Perhaps they can trade bandwidth bills with Netflix. I'm sure if they're willing to pay Netflix's bandwidth bill, Netflix would have no problem paying for their home DSL lines. Hell, maybe Netflix will even cover their mobile broadband accounts as well.

As for the rest of the op-ed, it's pretty funny. While they play up how Netflix "saves" $0.40 in postage by not having to use the mail, they ignore the fact that in order to stream movies, Netflix has to pay ridiculously high licenses. With disc rentals, it could buy one disc and rent it out many times. Not so with streaming licenses. It needs to pay a ton for those.

Then there's this bit of economic cluelessness:

Netflix argues that the marginal cost to the network providers of streaming a half-hour TV show to a residential customer is "one penny." This ignores the hundreds of billions of dollars in sunken network investments needed to create that one-penny marginal cost efficiency at the customer's end.Um, yes, it does. And as most any economics professor will tell you, you're supposed to ignore the sunk costs in understanding how a market prices things competitively. Telling the market to do the opposite is the very definition of an anti-market, anti-efficient solution.

Consumers tend to pay more when they consume more goods and services, and pay less when they consume less.And, contrary to the claims in the article, Netflix pays more when its users consume more. Again, will Sununu and Ford pay Netflix's bandwidth bill?

The reality is that Netflix and similar services want a free ride on the networks built with more than $250 billion in design, engineering, manufacturing, construction and maintenance -- a system that now provides broadband services to 95 percent of American households.Hey, you know what? I spent a lot of money building Techdirt. All of you now owe me money. Apparently that's how Sununu and Ford view market functions. If one party spends a lot of money on something, everyone else is just required to pay. Of course, back here in the real world, that's not how things work. Various broadband companies (with massive taxpayer subsidies, by the way) built out broadband networks because they knew it would be profitable to do so. They made their bet and made their deal. Now they're trying to change the deal by pretending that someone's not paying. They're lying. What they really want is for service providers to pay twice for the same bandwidth. Netflix is already paying for its bandwidth. Consumers already pay for their bandwidth. Sununu and Ford (and really, the telcos they represent) are really trying to get Netflix to pay again, pretending that they should pay for the bandwidth that consumers already paid for, even though Netflix is already paying for that bandwidth. This is about trying to double charge.

If broadband providers are so hard up for cash, then just let them raise rates. Nothing is stopping them from doing that. But that's not what this is really about. This is about trying to force Netflix to double-pay for consumers' bandwidth as well.

So, once again, John Sununu and Harold Ford Jr.: since you insist that Netflix is getting a free ride, will you pay Netflix's bills for the rest of the year? Or will you pull a Mike McCurry and simply ignore this simple challenge and go on pretending that Netflix doesn't pay?

Filed Under: bandwidth, broadband, economics, free ride, harold ford jr., john sununu, net neutrality

Companies: netflix

European Nations Wish To Ban Negative Thoughts Or Investments On Their Financial Position

from the towards-a-more-patriotic-hedge-fund dept

It seems that no country is immune to the sting of financial opinions. As we saw recently, S&P's decision to strip an "A" off their rating for the U.S. debt resulted in President Obama's dismissal of the rating ("We're still AAA."), Michael Moore's call for something a bit more drastic ("show some guts and arrest the CEO of Standards and Poors") and, finally, the Senate Banking Committee's decision to explore its options, including a possible hearing involving S&P ("We won't arrest them. We'll just take them downtown to answer a few questions.")Being unable to graciously accept financial criticism isn't just an American problem, however. As several European nations continue their slide into bankruptcy, their respective governments have stepped up to do the only thing that makes sense: ban short sales on government-backed bank shares (following on a similar plan to ban negative ratings). It's yet another case of governments attempting to suppress expression it doesn't like (i.e., "We think failure is the most likely option.") through legislation. And as Matt Levine of Dealbreaker explains, there's a whole lot of unintended consequences to banning "sad thoughts about banks:"

This is hard to believe because all European banks are obviously well capitalized and any suggestion to the contrary is just rumor and speculation. But! Sometimes things go wrong. Sometimes banks need to raise money. When equity investors are staying away from them, sometimes they do this by selling convertible bonds...Oddly enough, the protectionist legislation meant to protect the banks from "evil" speculation will also work against their ability to raise funds in the future, which extends the damage from "just right now" to "an indefinitely longer period."

The short sale bans are mostly for just 15 days, but repeatedly changing the rules in the financial markets will have effects well beyond the brief share-price gains. If you're a convertible arbitrage investor, it's now pretty clear that you should never buy convertibles issued by a European bank, because you may not be able to hedge when you need to. Which can't be good for the banks' future capital raising needs.

Then there's this bit of extremely broad terminology coming from Spain's entry into the "the only correct position is a positive position" ban-happy sweepstakes:

This preventive ban affects any trade on equities or indices, including cash equities transactions, derivatives in regulated markets or OTC derivatives, that has an effect of creating a net short position or increase a previous one, even if on an intraday basis. A net short position means any position resulting in a positive economic exposure to falls in the price of the stock.In much simpler words: investors are not allowed to profit when stock prices dip. This also means that investors can't mix in a few shorts with the rest of their investments to insulate themselves against price drops. Or rather, that they can do that, but only if the end result of the investments is that they lose money when stock prices fall. Spain, it would seem, is only going to allow bullish investments despite the realities of the market, and it will be watching this on a day-to-day basis, if the language above is to be believed. Adios, bear market day traders!

France ties things down even further in its extensive AMF document:

3 - Is an investor allowed to create a net short position in one of the securities concerned by using derivatives?France is also savvy to other devious, speculative moves as well:

No, investors are not allowed to use derivatives to create a net short position; they may only use derivatives to hedge, create or extend a net long position.

6 - Are trades in index derivatives allowed where the basket of securities includes one or more of the securities concerned?Again, this overly broad ban against speculators who have the audacity to express their lack of confidence in a financial system via their market activity will also steamroll "legitimate" investors who are just looking to "not lose money," as Levine points out:

a) Investors exposed to the equity market are allowed to hedge their general market risk by trading in index derivatives. In this context, the AMF accepts the marginal net short positions in the securities concerned that may result from that trading in index derivatives.

b) Trading in index derivatives for any other purpose than hedging general market risk is not allowed unless the resulting net short positions in the securities concerned are offset by long positions.

We wonder how you would test whether a net short position in an index derivative is for the purposes of "hedging general market risk" or for the purposes of "profiting on spreading false rumors" (or other non-legitimate purposes, like hedging specific market risk). Presumably anyone shorting European indexes does so because they don't want to lose money when the market goes down. Even speculators.Oh, and one more thing: these bans are still in effect if you're a citizen of these short-sale-banning countries, no matter which country you actually reside and/or do business in:

The Decision applies to any natural or legal person, French or foreign, regardless of whether trading takes place in France or in another country, or on a regulated market or not.All of this ridiculous legislation is due to various governments suddenly developing very thin skin when investors insult them tangentially with their financial decisions and opinions. There's nothing to be gained by banning short sales and plenty of unintended consequences to unleash into an already-disrupted marketplace. Levine sums up their attitude this way:

You take shorting of bank shares as a personal affront, and your goal is not to have functioning markets but just to prove that you’re tough.While I'm sure most governments would love all of their citizens to believe that their respective nations will overcome all odds and rise to greatness once again, in the meantime, investors are still going to bet on what is likely, rather than just wrapping themselves in the flag and throwing their money into whatever the legislative body deems to be proper, patriotic investments.

Filed Under: debt, economics, europe, markets, opinion, short selling, sovereign

The Latest Entrant Into The Economically Clueless, Luddite 'Internet Is Evil' Book Category

from the it-must-sell-well dept

Last we heard from Rob Levine, he was saying that people in the music industry shouldn't pay attention to what's popular on file sharing networks, because you can't learn anything from that. That was when he was executive editor of Billboard, and clearly was trying to defend Billboard's obsolete listings of what was popular. Very, very shortly after that heOf course, that's fascinating, since pretty much every study we've seen shows that the market for films and music has increased, and while for newspapers it has shrunk, that's unfairly limiting the market to the paper side. The market for news has continued to grow. Most of Levine's article seems to be made up of typical wishful thinking, carefully choosing how he defines markets, and a strong dose of traditional economic fallacies, with just a pinch of luddism. The article opens with the classic trick of pretty much anyone who's data can't back up what they're selling: use random correlations, rather than any evidence of a causal relationship. So, he talks about the declines of NBC, EMI, the Washington Post and MGM. And, somehow, that's proof that the internet is at fault. I won't go into each case, but there are many, many other reasons why each of those four companies ran into tough times recently, almost none of which has to do with the internet (and much of which had to do with ridiculously bad management).

From there he makes a massive leap to basically blame the tech industry for the entertainment industry's problems. Stop me if you've heard this one before. Apparently, you see, The Pirate Bay, Google & the Huffington Post sucked every other industry dry. This, of course, is not true. It's a made up scare story for entertainment industry executives and politicians. I mean, this kind of scare mongering has been debunked so many times that you'd think Rob must have to pay someone for rehashing such old news. Let's dig into this just a bit:

Over the past decade, much of the value created by music, films, and newspapers has benefited other companies – pirates and respected technology firms alike. The Pirate Bay website made money by illegally offering major-label albums, even as music sales declined to less than half of what they were 10 years ago.The Pirate Bay made a tiny amount of money -- barely a blip on the radar -- and given the continued research showing that those using sites like The Pirate Bay tend to be the industry's best customers, it's entirely clear (unless you are willfully ignorant) that the issue is a business model problem, where the labels failed to offer what consumers wanted. Furthermore, since he brings up "music sales," he's flat-out wrong. Sales of recordings may have dropped, but if you actually look at the real market which Levine conveniently ignores, which includes live, publishing, advertising, direct-to-fan and others, you discover that the money that actually goes to musicians has gone up tremendously. Sure, the record labels are suffering, but that's because they set themselves up to focus only on the part of the business that got disintermediated.

YouTube used clips from shows such as NBC's Saturday Night Live to build a business that Google bought for $1.65bn.Ah, the industry's false line again. YouTube provided free software and free bandwidth (at a huge expense to the company) and combined that with a large community to become the defacto place online for video. Lots of smart folks -- including NBC's Saturday Night Live, eventually learned to embrace that and use YouTube as a tool to gain viewers. In fact, if you want to look at who benefited more from SNL's videos showing up on YouTube, there's a pretty strong argument that it was SNL... not YouTube.

And the Huffington Post became one of the most popular news sites online largely by rewriting newspaper articles.Nice line. If only it were true. It's not. The Huffington Post launched with a ton of new and unique content from lots of people. Huffington called in a bunch of favors and had a ton of her famous friends writing for the site from day one. On top of that, the company has a large reporting staff that does plenty of original and unique reporting -- much of which accounts for its traffic. Yes, it also does some aggregating of content -- but nothing that any other news publication couldn't do as well. If it's really true that HuffPo somehow hurt other media, they could just tack on the same sort of aggregating. Anyone who claims that HuffPo became popular by rewriting newspaper articles is lying.

This isn't the inevitable result of technology. Traditionally, the companies that invested in music and film also controlled their distribution – EMI, for example, owned recording studios, pressing plants, and the infrastructure that delivered CDs to stores.I read this and all I see is that EMI is the horse buggy maker, who invested in wooden wheels and buggy whips just as the automobile was coming around. Look, if you invest in the parts of the business that become obsolete in the digital age, you kinda deserve to die. I'd hate to live in Levine's world where the buggy maker should have been able to stop the automaker. We had our red flag laws that required people to walk in front of automobiles waving red flags, and everyone learned they were stupid.

But, Levine thinks red flag laws are the answer to saving his incompetent buddies in the entertainment industry. You see, he blames one of the few good regulations out there, which he hopes gets taken away:

The internet changed all this, not because it enables the fast transmission of digital data but because the regulations that enable technology companies to evade responsibility for their business models have created a broken market. Scores of sites now offer music, while hundreds of others summarise news. Part of the problem is rampant piracy – unauthorised distribution that doesn't benefit creators or the companies that invest in them. It also puts pressure on media companies to accept online distribution deals that don't cover their costs.Anyone who thinks that the market didn't change because of the ability to more efficiently distribute data is making a joke. But, let's go on. Levine is, again, misrepresenting reality. The laws he's talking about -- mainly the DMCA's safe harbor -- do not allow tech companies to evade responsibility. Levine is, again, being intellectually dishonest. The safe harbor merely means that liability is properly applied to the actors actually doing the infringement. Apparently Levine prefers to blame Ford for any car accident.

As for that last line about "pressure on media companies to accept online distribution deals that don't cover their costs," that's a howler. Just take a look at the "deal" that Pandora has for streaming music, which has set up Pandora to never be profitable. And what "costs" do the record labels have for those deals? It's a sunk cost. They recorded the album and they just hand over the digital files to Pandora. No marginal costs at all.

But the underlying issue is that creators and distributors now have opposing interests. Companies such as Google and Apple don't care that much about selling media, since they make their money in other ways – on advertising in the first case, and gadgets in the second. Google just wants to help consumers find the song or show they're looking for, whether it's a legal download or not, while Apple has an interest in pushing down the price of music to make its products more useful. And this dynamic doesn't only hurt media conglomerates – it creates problems for independent artists and companies of every size.Another favorite of the entertainment industry. It sounds good if you aren't actually thinking this through. But there's a weasel phrase in there that lets Levine say something that he can insist is true, while it's totally and completely misleading. He says they don't care about "selling media." But that assumes that selling media is the only way for the entertainment industry to make money. Google and Apple care very much about making sure that content creators get paid, because they need content creators to keep making money to keep producing works (which, by the way, is happening, as we have record numbers of new music, movies, news and other products coming out each year -- a fact that Levine seems to completely ignore). But they know that there are better ways to get them paid than just "selling media." In fact, when you just look at the music industry alone (the industry Levine should know best), he must know that actual artists are now making significantly more than they did in the past, thanks to the industry shifting away from "selling media" to other business models.

Then he jumps in with the luddite's favorite line about how everyone who disagrees with him tosses out "information wants to be free." Of course, as Cory Doctorow pointed out last year, the only people who seem to toss out that line are entertainment industry execs pretending that's what people who disagree with them say.

The crux of Levine's argument (and the title of his book) is that all of this shows the problem of "free riders." This is another popular entertainment industry trope, which sounds good... other than the fact it's economically clueless. Yes, there are certain areas of economics where free riders can be a problem. But there are also such things as positive externalities and economic growth created because of free riders. There's a serious book to be written on the subject, but it's not this one.

Certainly, copyright laws need to be updated for the digital age. Many reformers say they favour protection, but view any attempt to enforce it as unacceptable. This doesn't make sense: a market can't be based on voluntary payments, and laws don't work if they can't be enforced. There needs to be some penalty for illegal downloading, although slowing the access speed of a lawbreaker makes more sense than cutting their account entirely. By the same token, why should internet users be allowed to access sites that clearly – and that last word is important – violate UK law? If the UK simply declines to enforce its laws online, it will leave many of its businesses vulnerable as the internet becomes more important to commerce in the years ahead.Note the implicit -- but false -- assumption in there. Without copyright, the only business model is "voluntary payments." That's funny, I didn't realize I had ever been "forced" to pay for all of those CDs, concerts and movies... A market is always based on "voluntary" transactions between willing buyers and sellers. That's the definition of a market. How can he say otherwise?

I'm guessing he really means "voluntary" in the idea of "tips" or "donations," but that again presumes (totally falsely) that the only way to make money is from the direct sale of media. It's not. And he must know that.

Honestly, for all the trouble I've given Levine in the past, I always thought he was pretty sharp on the larger issues. But this column (and, I presume the book it advertises) seems to have simply taken all the tropes, ignored all the data, misrepresented wherever possible, and packaged it all together under a silly economically ignorant title. I'm sure it'll sell just great. Thankfully, though, if you read through the comments on his article, nearly every one of his ridiculous statements is dismantled item by item. Ah, crowdsourcing to the rescue.

Filed Under: economics, free rider, internet, regulations, rob levine

Politicians, Innovation & The Paradox Of Job Creation

from the disruption-and-broken-windows dept

There's been a ton of talk from politicians lately about the importance of "creating jobs." This comes from both major political parties, of course. We've seen the Democrats jump heavily on the jobs agenda and the Republicans have been hyping up their ability to create jobs as well. A few months ago, This American Life produced a fantastic episode on the hilariousness of politicians claiming that they're going to "create" jobs, with a focus on Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker (one of the few stories about him that has nothing to do with unions).All of this talk about "job creation" from politicians has really been bugging me... with the only really "honest" politician I've seen being the totally ignored Presidential candidate and former New Mexico Governor, Gary Johnson. After the National Review praised him for being "the best job creator of them all," (based on jobs numbers associated with all the GOP Presidential candidates), rather than accepting the cheap political accolade, Johnson responded by rejecting the crown:

"The fact is, I can unequivocally say that I did not create a single job while I was governor."Instead, he noted that it was "entrepreneurs and businesses" that created the jobs, and all he tried to do was keep obstacles out of the way.

Still, it is true that governments can create jobs. It's just that they're almost never the jobs that actually help the economy. The government can hire 20 million people to move piles of dirt around or to just sit around if it wants. That will "create jobs." But it won't be good for the economy, because those people are not productive for the economy. They won't be adding value or producing something of value that expands the economy.

This, of course, was famously explained a century and a half ago by Frederic Bastiat, who explained the fallacy of the broken window as an economic or "jobs" stimulator. And, yet, it's still oh so tempting for politicians to jump on this train. But the problem for those who buy into the "broken windows fallacy," is that they make really bad decisions on "jobs," because they create the easiest jobs to create, which will almost always add the least value to the economy (and most likely take away value from the economy).

It's why you get amazing statements from President Obama (who really must know better) in which he talks about ATMs meaning fewer jobs for tellers and auto check-in kiosks at airports that mean fewer jobs for airline employees. But this turns out to be wrong in oh-so-many ways. First, it's just wrong on the facts:

At the dawn of the self-service banking age in 1985, for example, the United States had 60,000 automated teller machines and 485,000 bank tellers. In 2002, the United States had 352,000 ATMs--and 527,000 bank tellers. ATMs notwithstanding, banks do a lot more than they used to and have a lot more branches than they used to.It's "easy" to claim that technology "destroys" jobs, but it's never the case in practice. It may change jobs, but increased efficiency creates jobs through economic growth. There are all sorts of complex economic proofs of this in action, but the simplest way to understand it (and there's lots of both empirical and formulaic proof to back this up) is that when you increase efficiency, you can produce more for less, and thus, by the very definition, you have increased the size of the overall pie. Now plenty of people can (and do!) quibble about how that pie is divided and allocated, but arguing that jobs are destroyed by technology is a red herring.

It's for that reason that I'm a bit surprised to see Jeff Jarvis more or less jumping on this bandwagon by claiming that "we're going to have a jobless future":

Our new economy is shrinking because technology leads to efficiency over growth. That is the notion I want to explore now.While I agree with Jarvis on many, many things, he's missing half of the equation here, and doing a sort of reverse "broken window fallacy." He's looking at jobs that are changing, but not looking at the massive new opportunities it creates. Eric Reasons points me to my own post which touches on this.

Pick an industry: newspapers, say. Untold thousands of jobs have been destroyed and they will not come back. Yes, new jobs will be created by entrepreneurs -- that is precisely why I teach entrepreneurial journalism. But in the net, the news industry -- make that the news ecosystem -- will employ fewer people in companies. There will still be news but it will be far more efficient, thanks to the internet.

Take retail. Borders. Circuit City. Sharper Image. KB Toys. CompUSA. Dead. Every main street and every mall has empty stores that are not going to be filled. Buying things locally for immediate gratification will be a premium service because it is far more efficient -- in terms of inventory cost, real estate, staffing -- to consolidate and fulfill merchandise at a distance. Wal-Mart isn't killing retailing. Amazon is. Transparent pricing online will reduce prices and profitability yet more. Retail will be more efficient.

It's easy to look at how jobs appear to "disappear" in a dynamic market. Whether it's the tellers President Obama is talking about, or the "journalists" that Jarvis talks about. But that ignores all of the new jobs created around the new efficiencies. Take, for example, the fears that a telephone switching network would wreak havoc on our economy, decades ago. After all, telephone companies employed thousands of operators whose job it was to "connect calls." Automate that, and all of those women (and they were predominantly women) were "out of work." Devastating, right? Well, no, actually. Not at all.

A switched telephone network not only made the phone system more valuable and useful (increasing its usage), but opened up all sorts of new opportunities for businesses and jobs. At a basic level, you could just note that call centers were suddenly possible, as was the ability to do customer service (and, annoyingly, telemarketing) on a large scale. But, it also did much more. A switched telephone network also paved the way to an eventual internet system, which has led to a huge revolution, millions upon millions of jobs, and the fact that you are reading this today.

The idea that technology leads to efficiency over growth is preposterous. Efficiency is growth. But it's not always obvious how or where that growth occurs.

And that's why I think there's something of a paradox of job creation. The job creation we really want for the economy is the job creation that initially looks bad. It's the job creation that worries Obama and Jarvis, in that they believe it's somehow "taking away jobs." And yet, it's not. It's actively creating more jobs -- it's just not as obvious how or where, but they are being created, without question. Instead, the focus is put on the exact wrong kinds of jobs. You hear things about stimulus projects that grant money or protectionism to certain industries. On the face, that appears to create jobs, because those companies that are recipients of that support "hire" more people. But it's at the expense of productive and economic growth that would create real long term jobs and real long term opportunity.

So the best way to create jobs is the politically impossible plan of increasing efficiency, which may appear to replace jobs, even as it's creating many more. It means allowing real competition to take place, rather than propping up a few big legacy players. It means supporting true innovation, through encouraging startups and entrepreneurship, rather than rewarding the legacy players who seek to hold back the innovators. Job creation is a paradox. Anything politicians do to try to force it almost always does the opposite.

Filed Under: broken windows, economics, efficiency, job creation, jobs, politicians, politics, productivity

When Innovation Meets the Old Guard

from the don't-let-them-learn-too-much dept

You've probably heard of Khan Academy, the online lessons that have been praised so highly. Wired recently put up an article on how it's a complete game changer, and how children have been able to advance at a blistering pace using their materials. So what does the public school system think of it?So what happens when, using Khan Academy, you wind up with a kid in fifth grade who has mastered high school trigonometry and physics—but is still functioning like a regular 10-year-old when it comes to writing, history, and social studies? Khan’s programmer, Ben Kamens, has heard from teachers who’ve seen Khan Academy presentations and loved the idea but wondered whether they could modify it “to stop students from becoming this advanced.”I'll just let that sink in for a moment.

It's not an uncommon phenomenon. People get so caught up in "the way things are done" that they can't possibly comprehend any other way of doing things. Therefore, when you show them a child learning faster than his or her peers, the focus is not on how fantastic it is, but on how we'll be able to keep that child in the same class as other kids their age. Why is it necessary to group kids by age? Because it's just what we do. When a child is bumped up a grade, why do we do it for all subjects at once, instead of each subject separately? Because it's just what we do. The educational system was created to teach children; now it exists to perpetuate the current educational system.

It's hard not to equate this same thinking with the current dreadful state of copyright. You can show how an artist is making more money than they ever had before by encouraging sharing rather than sending in the lawyers, and your average maximalist will say, "It's great that they are making more money, but how do we keep control of the content?" In doing so, they put maintaining the status quo ahead of attaining the result that the system was designed to encourage. The copyright system was created to promote the progress of the arts; now it exists to perpetuate the copyright system.

Even our justice system is not immune to this kind of thinking. Laws against child pornography were created to prevent the victimization of children, now we use them to try to ruin the lives of children. We threaten vegetable growers, arrest DIY roofers, and send SWAT teams after orchid importers and raw milk sellers. Our system of law was created to promote justice; now it exists to make criminals.

Does teaching every child the exact same lesson at the same age serve our educational needs? Will arresting people who merely link to infringing videos give artists an incentive to create? Is the patent thicket around mobile phones to the benefit of consumers? Do we all sleep easier at night knowing that a 66-year-old man is locked away in federal prison because some of his orchid paperwork was missing?

If we ever want our institutions to serve us rather than serve themselves, it's time to focus on what we had hoped to gain from them in the first place, and to question every assumption that underlies them.

Filed Under: economics, innovation, legacy companies

Rent Is Too Damn High Guy Increasing Rent For Others Because His Rent Is Too Damn Low

from the how-markets-function dept

Lots of people got a kick out of the "rent is too damn high" guy, Jimmy McMillan, running for governor of New York last year. He certainly was entertaining. However, it appears that McMillan's own rent may be too damn low... meaning that he's a part of the damn reason that the rent is too damn high in New York. It turns out that McMillan's landlords are trying to evict him from his rent controlled East Village apartment for which he pays $872.96 a month. That's crazy cheap for an apartment in the East Village. What he doesn't seem to recognize is that when the laws keep the rent on certain properties artificially low compared to the market, that's a huge part of the reason why "the rent is too damn high" for everyone else. If McMillan really wanted to lower the rent, he'd work to get rid of widespread rent control, as that would help drive down the prices of rent in certain areas.Filed Under: economics, jimmy mcmillan, rent, rent is too damn high

'When Stuff Is Free, We’re More Likely to Buy'

from the oh-really? dept

Scott Wetterling was the first of a bunch of you to send in one of the many stories about how when 7-Eleven offers free slurpees, their sales of slurpees goes up. They say this is "odd behavior," but I don't buy that all. Free has been a compelling part of getting people to buy stuff for ages, even if that involves buying what is free. We've certainly seen this in other fields as well, such as when Cory Smith took his free MP3s off of his website... and immediately saw his iTunes sales plummet. People berate the use of free because they don't understand how it works. And, then, when it does work, they describe the behavior as "odd." Perhaps it's not odd at all once you realize how it works.The Greatest Trick The NYTimes Ever Pulled Was Convincing The World Its Paywall Exists

from the paywallonomics dept

It's no surprise that we've been pretty big critics of the NYTimes' paywall strategy -- not because we don't want the NYT to make money, but because we don't think it's a particularly good strategy. However, people are now claiming that it's undeniable that the NYT's paywall has been a huge money-making success. And looking at the numbers, I'll admit that they're way more impressive than I expected -- by a lot:The Times introduced digital subscription packages on NYTimes.com and across other digital platforms in Canada in mid-March and globally at the beginning of the second quarter. Paid digital subscribers to the digital subscription packages totaled approximately 224,000 as of the end of the second quarter. In addition, paid digital subscribers to e-readers and replica editions totaled approximately 57,000, for a total paid digital subscribers of 281,000 as of the end of the second quarter.This is definitely more than I expected, and it does show a much faster trajectory to get to those results than its last paywall. The Forbes account of this notes that, as a conservative estimate, this could mean an additional $40 million per year for the NYT's topline. Separately, it also points that the loss of traffic from the paywall might not even be noticeable, claiming that it received 33 million unique visitors per month which was "in line with its average for the preceding 11 months."

In addition to these paid digital subscribers, as of the end of the second quarter of 2011, The Times had approximately 100,000 highly engaged users sponsored by Ford Motor Company's luxury brand, Lincoln, who have free access to NYTimes.com and smartphone apps until the end of the year, and approximately 756,000 home-delivery subscribers with linked digital accounts, who receive free digital access.

That's all impressive. And once again, I'll say that it's much better than expected and, perhaps, I misjudged the potential for the paywall. That said... digging into the numbers, I'm still skeptical for a variety of reasons. First up, this is a drop in the bucket. Even if the company earns an extra $10 million per quarter from this, the paper also lost $114 million. But, that's a little misleading on its own, as it includes a giant writedown.

But, the real question is what could the NYT be doing instead. It made $84.6 million in the quarter from digital advertising alone, way more than it made from subscription fees. But the growth there was tiny -- only 2.6% at a time when I know companies are looking to do really interesting digital promotions and will pay for them. And while the company says that its unique visitors were "inline" with previous 11 months, what you want to hear is that the traffic is growing. The use of unique visitors is interesting, since most ad campaigns work on a CPM basis, where views are what counts -- and other estimates suggest that pageviews have dropped noticeably. This would make sense, actually. Since the "paywall" still lets people view up to 20 pages before it sorta stops you from seeing any more, you could see how the same number of people would go there, but actual pageviews would decrease.

But what if, instead of focusing on the paywall, the NYT had focused its efforts on adding more direct value to the site itself, to (a) get more visitors to the site and (b) to keep them there longer, viewing more pages and doing more? At the same time, if they started looking at more creative, premium sponsorship/ad campaigns, I could see how they could have spent the same resources in a much more scalable growing arena, rather than having it go into a more limited paywall. That is, if they'd focused on continuing to grow traffic and creative ad campaigns, that's something that will continue to grow. How many more subscribes will they get with the paywall? If people haven't subscribed yet, how much more will it take to get them to subscribe, when it's pretty clear that anyone can get around it. I have to admit I've never even noticed the paywall at all in all my surfing.

Early on, I called the NYT paywall the Emperor's New Paywall, but perhaps a more interesting point is that, as with the Emperor, the NYT's has done an amazing job convincing lots of people that the paywall is really there and that they have to pay to view articles on the site. It's a great trick. But can it last? People, who aren't paying now, don't have much reason to start paying, so I'd expect that the subscribers will plateau at some point relatively soon. I'd imagine that the younger generation is barely paying at all. The strategy brings in some money now, but it seems like a pretty small amount for selling out future growth opportunities.

Filed Under: economics, journalism, paywalls

Companies: ny times

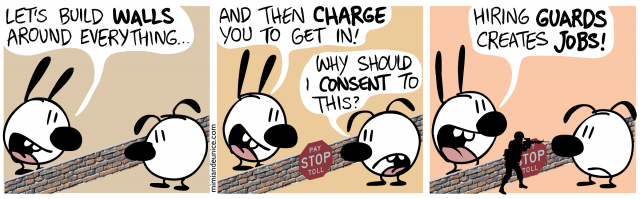

Gatekeepers And The Economy

from the jobs-justify-anything dept

I was actually thinking about the TSA when I wrote this, but it applies just as well to IP.

Filed Under: economics, gatekeepers, jobs, walls