Culture is Anti-Rivalrous

from the it-increases-in-value-the-more-it's-used dept

Economists talk about rivalrous and non-rivalrous goods, but Culture is neither rivalrous, nor non-rivalrous; it is anti-rivalrous.

I. Rivalrous

Rivalrous goods diminish in value the more they are used. For example, a bicycle: if I use it, it gets me from here to there; if you use it, it gets me nowhere. If I acquire your bicycle, you don't have it any more. Only one of us can have the bicycle at one time. We can share it to a limited extent, but the more it's used the less it's worth; it gets dinged up and wears out. The more people use the bicycle, the less utility it has.

If I steal your bicycle, you have to take the bus

All material things - things made of atoms - are rivalrous, because an object cannot be in two places at the same time. Everything in the physical world is rivalrous, even if it's abundant.

A commons is a rivalrous good. Hence the "tragedy of the commons": the more people use a square of land, the less valuable it is to each of them. The grass gets eaten too fast to grow back, the soil can't handle the incoming rate of sheep shit, and degradation ensues.

Fig. 1: a lovely day for grazing on the commons

Fig 2: Tragedy strikes

Rivalrous and non-rivalrous are often confused with scarce and abundant, but they're not the same thing. Air is abundant, but it is still rivalrous - some "users" could make it toxic for the rest of us, because air is not infinite. Land and water are so abundant in North America that Native Americans couldn't imagine owning or depleting them, and look what happened. We treat the oceans as infinite, but they are not; human pollution and exploitation is killing ocean life. We also pollute the vast ocean of air - hence acid rain. Air and oceans are commons.

Commons are commonly-held rivalrous goods. Because they are rivalrous, some uses (or over-use) can poison them or otherwise diminish their value. For that reason, Commons(es) actually merit rules and regulations.

But Culture is not a commons, because Culture is not rivalrous and can't be owned.

II. Non-Rivalrous

Non-rivalrous goods, as their name implies, don't diminish in value the more they are used. A favorite example of a non-rivalrous good is the light from a lighthouse. It shines for everyone. No matter how much you look at it, I can see it too.

Everyone can see the light from the lighthouse...

This is a pretty good example, but it's not quite right. Theoretically, if enough tall boats are in the harbor, they actually can crowd out your lighthouse light.

...except when they can't. Once again, too many sheep ruin everything.

Consider sunlight in Manhattan; yes, the sun shines for everyone, but if they build a high-rise next to your apartment you won't see it any more. There's only so much sunlight that hits a certain area, and that light is rivalrous. You can always move, of course - except land, while abundant, is definitely rivalrous and not infinite, so you'll have to engage in some rivalry to do so.

The light metaphor has another problem: is light a particle, or a wave? If it's a particle, then light is rivalrous. If it's a wave, then it's not.

III. Anti-Rivalrous

Anti-rivalrous goods increase in value the more they are used. For example: language. A language isn't much use to me if I can't speak it with someone else. You need at least two people to communicate with language. The more people who use the language, the more value it has.

Which language do you think more people would pay to learn?

- English

- Esperanto

- Latvian

More people spend money and time learning English, simply because so many people already speak English.

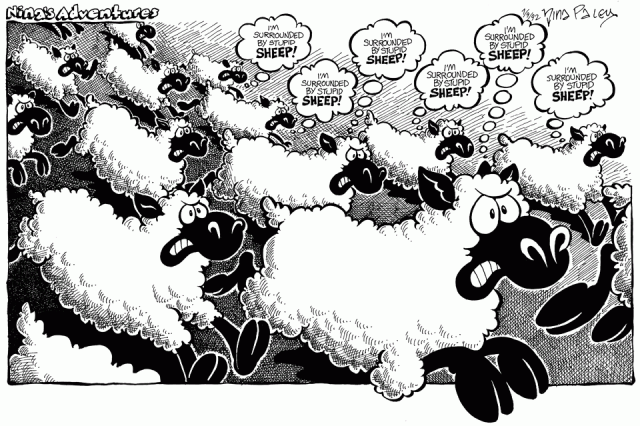

Social networking platforms increase in value when more people use them. I use Facebook not because I love Facebook (I certainly don't), but because everyone else uses Facebook. I just joined Google+, and will use that instead of Facebook if enough other people use it. If enough people flock to yet another platform, I'll use that instead. Meanwhile I love Diaspora in principle (I was an early Kickstarter backer, before they surpassed their initial $ goal), but I don't use it, because not enough other people do. When it comes to social networks, I am a sheep.

A classic "Nina's Adventures" comic, which I only realized was anti-rivalrous a few years ago. ♡ Copying is an act of love. Please copy and share.

Cultural works increase in value the more people use them. That's not rivalrous, or non-rivalrous; that's anti-rivalrous.

IV. Some Exceptions That Prove The rule

I know what you're gonna say now: "what about my credit card number? That doesn't increase in value if it's shared!!" That's right, Einstein, because your credit card number is not culture. Here are two things that aren't made of atoms and are nonetheless rivalrous:

1. Identity

2. Secrets

Identity is some mysterious mindfuck that my very smart friend Joe Futrelle says no one has satisfactorily defined yet. But whatever identity is, it's rivalrous. If more people were named Nina Paley and had my home address and social security number, I'd be screwed. But that should highlight that my name, home address, and social security number aren't culture. They may be information, but they're not culture. They don't increase in value the more they are used.

Secrets have power as long as they're secrets. They lose their power when they are shared. When I become conscious of some secret that's weighing on me, I share it with at least one other person (even if they are a confidante also sworn to secrecy): I can feel the secret's power diffused just by the act of sharing. Notice I use "power" here instead of "value." Secrets may be of little or no cultural value - most people don't really care who that guy slept with 6 years ago - but they can certainly have power, especially when used for blackmail. Which is why it's important they remain secrets, so they're not used for blackmail, or harassment, or any reason at all. Privacy is important. Because secrets aren't culture. Culture is public. Secrets are, well, secret. Until they're public, whereupon we get scandalous stories that are culture - humans love to gossip - but aren't secrets any more. The story might gain value, but the secret loses it.

Money vs. Currency

And how about money? Money is scarce, right? It has to be, or it doesn't work (thanks Wall Street & Federal Reserve for screwing that up). But currency has more value the more it is used! Would you rather have your scarce 100 Euros in Euros, or in giant immoveable donut-like stones on a remote island?

A large rai stone in the village of Gachpar

I remember when the US dollar was a valuable currency; markets all over the world wanted dollars, because they were so widely used and exchangeable. So you want your money to be scarce, but you want your currency as widely used as possible.

V. Conclusion

It's important to treat scarce goods as scarce, abundant goods as abundant, rivalrous goods as rivalrous, and so on. Wall Street treated money, a scarce and rivalrous good, as though it were infinite/non-rivalrous, and look what happened. Power companies, and the politicians they own, treat the environment, which is a rivalrous commons, as though it were non-rivalrous, and we have dying oceans and mass extinctions and other events you don't want to think about so much that you'll just get mad at me if I point them out here so I'll stop. The RIAA and MPAA, and the politicians they own, treat Culture, which is anti-rivalrous, as though it's rivalrous. They are doing for Culture what Wall Street did for the economy. If you want to help make this better, treat Culture like what it is: an anti-rivalrous good that increases in value the more it is used.

Addendum: Why do I say Culture is not a Commons?

Filed Under: abundance, culture, economics, non-rivalrous, rivalrous, scarcity

Why Piracy Happens: Because No One In Mexico Thinks Tron Legacy Is Worth Paying $136

from the economics dept

Earlier this year, we wrote about the absolutely wonderful, detailed and insightful SSRC Report on "Media Piracy," which made it clear (through actual research and data) that "piracy" is almost never a legal or enforcement problem, as many industry folks insist, but rather a business model problem. To drive this point home, Joe Karaganis, who put the report together, has written up a short article for the Huffington Post, putting the economic realities into clear and easy to understand terms:This may seem like an obvious conclusion but it is strikingly absent from policy conversations about intellectual property, which focus almost exclusively on strengthening enforcement. Nowhere in the industry literature or in major policy statements like the US Trade Representative's annual Special 301 reports will you find an acknowledgement of piracy's underlying causes: the fact that, in most parts of the world, digital media technologies have become much much cheaper without any corresponding increase in access to legal, affordable media goods. DVDs, CDs, and software in Brazil, Russia, Mexico, or South Africa, for example, are still priced at US and European levels, resulting in tiny legal markets accessible to only fractions of the population. Would you pay $136 for a Tron Legacy DVD (the relative price in Mexico, adjusted for local incomes)? How about a $7300 copy of Adobe's Creative Suite? I didn't think so.Karaganis explains why these firms may have incentive to do this, but notes that this completely goes against the official policy positions of those pushing for laws like PROTECT IP. What becomes clear is that PROTECT IP isn't at all about protecting content. It's about protecting and propping up the legacy business models of a few companies who don't want to adapt.

Filed Under: business models, economics, piracy

The Misconceptions Of 'Free' Abound; Why Do Brains Stop At The Zero?

from the free-is-not-a-business-model dept

Jim Harper points us to a blog post by a guy named Richard Muscat, supposedly debunking the problems of "free" as it comes to business models. Frankly his post is pretty weak. It rehashes a bunch of arguments that have been debunked plenty of times before, but since we keep seeing these arguments made, I figured I'd use Muscat's piece to explore why it is that those who don't understand the concept of free are condemned to make such bad arguments against it.The key problem, it seems, is that people who dislike the concept of free have this weird issue where they stop thinking once the big zero enters the equation. In the past, I've pointed out that it seems like some brains have a divide by zero error problem, where, once they see free as a part of the business model, they stop paying attention to the rest of the business model and just focus on the free part. But here's the thing, no one is claiming that "free" is the business model. People who discuss the value of free have always been talking about how you use it as a part of the business model. So arguing that "free" is not a business model is a strawman. No one is claiming that free, by itself, is a business model because that makes no sense. But Muscat takes things even further, by claiming that it's so bad that it's "harmful":

My contention is that “Free” as described and used in many contemporary web-based businesses is a non-business model that is not only broken, but actively harmful to entrepreneurship. Free rarely works, and all the times that it doesn’t, it undermines entrepreneurial creativity, destroys market value, delivers an inferior user experience and pumps hot air into financial bubbles.Don't hold back.

Free does not push you to create something evocative that users and customers are willing to commit to in the long term.Because no one has committed to Google long-term. And before that no one committed to radio. Or broadcast TV. Huh? Having a product that is "free to the consumer" does not mean people won't commit to it at all. In fact, if you put together a smart business model, it could be the exact opposite. All of the examples here involve cases where companies use free to bring in people and then sell that attention to advertisers. In those cases, they very much have the incentive to create something that makes people commit, or they don't have the attention to sell. It's only if you stop at the zero and don't follow through that you could possibly claim that business models that use free don't get customers to commit.

Free absconds on the entrepreneur-customer commitment: by asking for nothing you also promise nothing. Both parties can walk away because there is no relationship. On the other hand by asking for money (or some other form of commitment), however large or small an amount, you create a self-imposed drive to produce creative and valuable products because not doing so would mean letting somebody down.

As the title suggests, the book argues that software pricing shouldn’t be decided randomly. There are three big reasons for not doing this: first, you might be missing out on revenue; second, your product price says something about the quality and intended audience of your product; third, your price also sets an expectation of how much effort has gone into production and how much value a customer should expect.Not sure what that has to do with anything. I don't think anyone is suggesting that people randomly choose free as a price either. In fact, we've been quite careful to explain that the whole point of understanding the economics of free is so that you can understand when it's appropriate to use free and when it's not. That many startups don't understand when it's appropriate to use free is not a condemnation of free as a price. It's a condemnation of people not understanding the larger economics and how to put together a good business model.

Choosing Free as your product price runs the risk of attracting entirely the wrong audience for your product or service.Sure. But that's only an issue if you fail to plan out the rest of your business model. The implicit assumption that Muscat makes here, which is incorrect, is that the whole point of free is to attract an audience which might buy.

Although you may get tens of thousands of users, it is probable that those users are unlikely to ever consider paying you because by definition you have attracted people who are looking for free stuff. Reversing this decision later can be extremely painful: you will piss off your existing user base, potentially generating very negative publicity and you might need to start from scratch in terms of looking for the right audience.Right, but that's not a criticism of "free," that's a criticism of a bad business model built around the idea that free is just a trick to get people to upgrade. If that's your business model, then he's right that it could be a bad business model (though some companies, such as Evernote, have found that it works for them). But that's not a problem with "free." That's a problem with the rest of the business model.

At some point or another you will realise that you do need to create a revenue stream. If you end up in the situation I just described above, i.e. encumbered with an audience of people unwilling to pay for what you’re providing, you will be faced with a dilemma: start over and risk the bad press or try to squeeze some pennies out of a reluctant user base.Again we see the divide by zero issue, in which he implicitly assumes that free is implemented in place of a complete business model. That's not the fault of "free." That's the fault of a bad business model.

The latter is a slippery slidey slope that leads towards intrusive in-app advertising, pop-ups, link-baiting, shady affiliate marketing, email spam and a total lack of focus on user experience.Indeed. Those would be bad decisions built on a bad business model. I'm not sure what that has to do with "free" however.

The idea that things can be free is behind a lot of financial bubbles. In the late nineties we thought that we could get distribution and infrastructure for free and we got the dot com bubble. A couple of years ago we thought we could get loans and bank credit for free and we got the property bubble. In both cases we left something very important out of the equation: delivery costs in the former and ability to repay mortgages in the latter.That's an interesting and totally incorrect bit of historical revisionism. First, the dot-com bubble was a result of investors (and many dot-coms, themselves) having no real understanding of web-based business models. Early dot-com successes (some real, some imaginary) created a rush of investors eager to throw money at any company offering something on the web -- without ever looking at whether they even had a business model. And I've never seen a loan or credit -- or internet infrastructure, for that matter -- that was "free." Were there some companies that went to extremes during both bubbles? Yes. But there was no direct connection to "free."

If you’re putting together a business plan or a slide deck that claims there will be an initial period of “short-term loss” while you establish a user base which you will then monetise, just remember that that is exactly what most of the pre-2000 dot com business plans were like.And, um, it was also the basic business plan of all sorts of successful businesses going back through history. It was clearly the plan of Google, Amazon, Facebook and Twitter, for example. So what? If you have a smart business model behind it, it can work. If you don't, it will fail. Claiming that it is inherently flawed is wrong. Also, it's the very basis of pretty much the entire venture capital industry. The whole reason why startups need venture capital is to fund that initial period in which there are short-term losses. It's called investing in growth. Intel had to build fabs. Apple had to build computers. Those involved "short-term losses" to build the product. That's how these things generally work.

Almost never. Somebody always pays. If healthcare is free, your taxes pay for it. If the flight is free, the extras aren’t. If the search is free, the advertiser is paying.Um. That's the whole point of using free as a part of a business model. Of course someone pays. That's what we're describing here. It seems totally ridiculous to go on for paragraph after paragraph discussing how free is awful because no one pays... and then, at the very end, to throw in a "but someone pays!" Why didn't he consider those points earlier in the article?

The only time when Free can really work for you is if you set your sights on having a specific outcome: acquisition.Yeah, just like Google. And Facebook. And Twitter. Good grief.

Look, if you understand the economics behind digital goods, you can quickly learn that there are places where free makes sense. It makes sense when, if you don't go free, your competitors will and you'll lose all of your business. But no one has ever suggested that free, by itself, is a business model and if your debunking of "free" is based on that, it just means you've stopped your analysis too soon. Free is an important part of many, many, many business models these days and that's been true for many years as well. Free isn't bad. It can be used badly, but to condemn it, based on that alone, suggests someone hasn't thought things through.

Filed Under: business models, economics, free

Lady Gaga Says $0.99 Albums Make Sense, Especially For Digital

from the understanding-how-this-works dept

You may have heard that Amazon did a deal recently with Lady Gaga, in which it offered up her entire new album for $0.99. While Amazon did have some technical difficulties in making this work, it resulted in some mindless criticism, in places, that Gaga was "devaluing" her own work. We hear this argument all the time, when it comes to free music, as well -- where people suggest that giving away music "devalues" the music. This shows a fundamental misunderstanding of the difference between price and value. Just because something is cheap, it doesn't mean that the value is diminished.In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, where Lady Gaga is asked directly about this issue, she almost seems offended, and notes that, especially when it comes to digital, pricing an album at $0.99 is perfectly reasonable, since it helps spread the music. After being asked if she thought her album was "worth" more than $0.99, she emphatically replied:

"No. I absolutely do not, especially for MP3s and digital music. It’s invisible. it’s in space. If anything, I applaud a company like Amazon for equating the value of digital versus the physical copy, and giving the opportunity to everyone to buy music."This isn't too surprising, given Gaga's previously stated views on her use of free to get her music out there, as well as her encouragement of people to download unauthorized copies. However, it's nice to see her make this point again.

Now, to be fair, she also notes that Amazon covered "the difference" with these albums as part of a promotion -- meaning that she (well, her label) got more than $0.99, but that's a separate issue than the whole question of the "perception" from giving away the music at such a low price.

Later in the interview, she makes another point that we've been making for a while, which is that record labels certainly make sense for some people, but the exciting thing today is that you don't "need" the label any more. She points out that she certainly needs her label, which is great, but that many artists don't need to go that route, saying, "not everybody needs a record label" any more. She also points out that the really valuable thing she's done is build a really strong connection with her fans, and it's that kind of authentic connection that makes her audience so valuable. These are all points that plenty of us have been making for years, and it's great to see such a prominent musician making the same points.

Filed Under: business models, economics, free, lady gaga, music

RIAA Says There's No Value In The Public Domain

from the true-colors dept

While I've already written about the hearings for the Copyright Office concerning copyright on pre-1972 sound recordings, but I wanted to call out one particularly egregious and ridiculous statement from the RIAA. The RIAA's Jennifer Pariser claimed that there's no value to a work in the public domain. Apparently Pariser is unfamiliar with the works of Shakespeare. Or Beethoven. Is she serious? I mean, you could make the argument that it makes life more difficult to sell those works for the labels she represents, but those works have tremendous value. Pariser, of course, is famous for making ridiculous statements, sometimes under oath. Back when she worked for Sony-BMG she made some statements, on the stand and under oath, in the Jammie Thomas trial that were blatantly untrue. Only much later, after the jury had ruled, did the RIAA admit that Pariser "misspoke" while on the stand. One hopes she "misspoke" here as well, but I get the feeling she actually believes the blatantly incorrect statement she made.Filed Under: copyright, cost, economics, jennifer pariser, public domain, riaa, value

Companies: riaa

Microsoft Blaming 'Piracy' Rather Than Basic Economics For Its Struggles In China

from the econ-101-time dept

Steve Ballmer is the latest Microsoft exec to whine about how much "piracy" is costing the company in China, noting that they make so much less in that country than in the US, despite similar numbers of PCs being sold in each country. The mistake should be obvious to anyone who understands basic economics -- or anyone who's read the SSRC report on "piracy in emerging economies." That detailed study lays out, quite clearly, that the issue isn't "piracy," but business models and pricing. People in China, on average, make significantly less than people in the US, so it's no surprise that fewer people are willing to pay Microsoft's high prices. Automatically blaming the issue on "piracy" totally and completely misses the underlying reasons for the difference in revenue. It's a bit scary that someone like Ballmer doesn't seem to recognize this, because it suggests his strategy in China is not going to do much good at all.Filed Under: china, economics, piracy, steve ballmer

Companies: microsoft

Groupon... And The Difference Between Idea & Execution

from the all-about-the-execution dept

About a month ago, the folks at Planet Money did a nice podcast on the economics of Groupon. There's no doubt that there's a bit of a "coupon" bubble going on these days, with tons of companies crowding into the space, and (as the Podcast notes) a bunch of ex-Wall St. types jumping into the space with talk of creating derivatives on coupons/deals. At the same time, plenty of people have mocked Groupon and insisted that its model isn't sustainable and others can easily come in and kill Groupon. In fact, some of the Wall St. guys who stayed on Wall St. are saying that Groupon's value shouldn't be that high because anyone with a phone can copy them.Lots of people are discussing Felix Salmon's excellent analysis of the economics of Groupon, which is really more about the fact that Groupon has dominated the space because it executes well. That is, it's not about the idea, it's about the execution. The fact that it has remained dominant despite so many copycats shows that just copying isn't enough. This doesn't mean that Groupon will always be the best at executing (in fact, I doubt it will be). But it's not so simple as just coming in and copying.

This is an issue that comes up all the time when we talk about business and intellectual property. People who haven't built up businesses like this assume that all you need is the idea -- and if an idea can be copied, then the company can't succeed. But that ignores just how important the execution element is. Salmon talks about how hard Groupon works to make sure its advertisers are happy with the results, to a level beyond most of its competitors. However, I think there's another element of Groupon's execution that hasn't received nearly enough attention: how enjoyable it makes the whole thing for consumers.

Groupon employs a bunch of writers who work hard to make sure all of the deals are compelling, enjoyable and fun. It always amazes me how much people underestimate the value of the quality of the writing in Groupon's offers. However, where it really struck me was a few months back, when I was researching some newer competitors to Groupon -- in particular, newspapers that were offering deals directly to compete with Groupon. In theory, newspapers should be able to absolutely destroy Groupon. If you're just standing on the mountain looking down, and seeing who has the advantages here, it's clearly the newspapers. Newspapers already rely on local advertising and deals, and have established long-term relationships in the market. On top of that, newspapers employ a ton of (mostly) high quality writers as well, so they should be able to create similarly compelling content.

And yet, when I was looking at various newspaper Groupon clones, what struck me was how boring and dull their offers were. Even if the deals themselves were comparable (and they often weren't), they just weren't that interesting or compelling to read. And that's because the newspapers -- like the Wall St. analyst above -- are engaging in cargo cult copying, where they think that all that matters is copying the superficial idea -- while missing the secret sauce that goes into the less obvious execution.

As a final aside, the quality of Groupon's content highlights another key point that we've raised many times before: how "infinite goods" like content make scarce goods more valuable. In this case, the "content" created by Groupon's writers (and, yes, this is also an example of how advertising is content) is valuable. But no one's selling the "content." What Groupon is doing is using that good content to make the scarcity of the deals more valuable, making more people willing to buy them.

In the end, I will admit that I have my doubts about the overall sustainability of Groupon itself, but it's not because "the idea" is easily copyable. I'm just not convinced that Groupon can continue to execute as well, and some aspects of what it's offering have some elements of a fad written all over them. But claiming that the company is overvalued because the "idea" is too easy makes little sense.

Filed Under: content, coupons, creation, deals, economics, execution, idea, innovation

Companies: groupon

Key Economics Lessons For The Digital Era

from the things-to-remember dept

Jeff Jarvis has a series of short notes that he's put together on "hard economic lessons" for the news business, but many of them apply to pretty much any industry -- and it seems worth pointing some of them out for discussion:- Tradition is not a business model. The past is no longer a reliable guide to future success.

- "Should" is not a business model. You can say that people "should" pay for your product but they will only if they find value in it.

- Virtue is not a business model. Just because you do good does not mean you deserve to be paid for it.

- Business models are not made of entitlements and emotions. They are made of hard economics. Money has no heart.

- Begging is not a business model. It's lazy to think that foundations and contributions can solve news' problems. There isn't enough money there.

- No one cares what you spent. Arguing that news costs a lot is irrelevant to the market.

Filed Under: digital, economics, journalism, tradition

If You Can't Understand The Difference Between Money And Content, You Have No Business Commenting On Business Models

from the please-shut-up dept

I've been noticing a really silly trend lately, of copyright maximalists trying to "debunk" people who actually understand the economics of content, by trying to sarcastically equate money to content and then saying, "if it's okay to copy content then isn't it okay to copy money?" It's an argument stemming from pure ignorance, mixed with an unhealthy dose of smugness, and we should try to pop this bubble before it goes much further. In order to do so, let's take a look at a picture perfect specimen of this sort of argument from (of course), an IP lawyer (who else?) named James Gannon, who wrote "How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Copy," all about copying money. It's getting passed around by various copyright maximalists with comments about how "brilliant" it is.It's brilliant only if you don't understand all of the following: money, economics, copyright, business and value. If you understand any of those things, you might recognize that the analogy makes no sense. Misunderstand all of them... well, then I can see how this argument might make sense. It's also not a very original argument, because we see it all the time and it's been debunked before. But now that it's rising in popularity, let's dig in a little and see if we can explain how utterly ridiculous the comparison is.

Gutenberg did not invent the printing press so that it would be controlled in the hands a few rich and powerful central bankers who desperately cling to outdated business models. With the advent of digital technologies, everyone can and should be free to copy their own money.I see what you did there. Of course, here's the key thing: money and content are two totally separate things. We write about content frequently, but we also write about money quite a bit, and in fact, have spent an awful lot of time discussing what money is, how it might change and where it's heading. Traditionally and classically, money is defined as three things: a store of value, a medium of exchange and a unit of account. Content is none of those things. You can't compare the two, because they're nothing alike.

And here's the key point that the "har har copy money durrr" crowd doesn't seem to comprehend. Money is a scarcity. They used to go on and on about how content was the same as a car ("you wouldn't steal a car") but the switch to using "money" as the example is because enough people have so debunked that argument by explaining the differences between scarce goods and abundant goods that they (mostly) don't even try any more. But by switching to money, they show that they don't understand what they were being taught. They thought people were only focusing on tangible goods, not scarce goods in explaining the differences. Tangible goods are scarce, but not all scarcities are tangible goods. Money is a perfect example of that.

Money is scarce. It's not scarce because there are a limited number of bills. In fact, most money isn't in bill form at all, so that's clearly not it. Money is scarce because of that first characteristic listed above: it's a store of value, and money, by itself, doesn't create any additional value. The overall value is a scarcity and the money is a representation of that value. You can print more money, but that creates inflation, because the overall value remains the same. That's not the case with content. Contrary to what some claim, getting more content on the market does not take away value. In a culture where shared culture and shared cultural experiences are highly valued, the fact that you can copy content makes it even more valuable. It makes it easier to share that cultural experience.

In other words, content can create new value. Money does not. Money is a store of value. Content is not. Pretending these two things are the same is wrong and will make you look foolish.

Don't get me wrong. I love the bank notes that are created by the Bank of Canada (BoC). In fact, I consider myself to be one of their biggest fans. Even though the BoC will try to stop me if I try to make my own copies of their bills, they should really be flattered.Right, except all of that is simply wrong and shows ignorance of the basic factors of both content and money as described above. When you copy money, you are actually decreasing the value of money. That's not true of content. When you share content with people, you increase the market opportunity for the content providers. That's not true with money. Pretending otherwise is either ignorance or propaganda.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery and I only want to share their work with my friends and family. By allowing me to make copies of their works, my friends might become fans of their currency too. Everyone knows the value of a currency is based on its demand so why not try to get as many fans as possible?

Gannon's piece goes on from there, continuing to pretend that he's sarcastically making a point. It's a really pointless argument, and doesn't make him look particularly intelligent. If he wants to debate actual economics or business models, plenty of us would be happy to do so. Instead, making arguments like this is just silly and doesn't make his point. It just makes him look like he has no real argument, and has to resort to pure sophistry.

Filed Under: business models, content, copying, economics, money, scarcities