Harvard Newspaper Staff Apparently In Need Of A Lesson On Copyright Basics

from the don't-they-have-a-law-school-there? dept

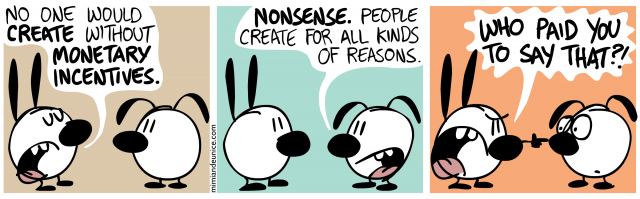

Copycense points us to an editorial in the Harvard Crimson apparently supporting the MPAA's new demands to universities that they need to police their local networks to stop students from file sharing. The editorial has tons of problems -- starting with the fact that it ignores that the MPAA lied to get the law passed in the first place. But the editorial has much more serious problems, and makes you wonder what they're teaching students at Harvard these days. Let's focus on this paragraph:Our support for the MPAA's actions is based on our belief that the unauthorized downloading of music, movies, and television programs, although easy, is questionable at the most basic level. In our postindustrial economy, the protection of intellectual property rights is important for several reasons. First, these rights must be safeguarded in order to provide an incentive for innovation. Without any guarantee of legitimacy, entrepreneurs will have no motivation to create new intellectual property, as it could be stolen at any time.Really? Perhaps the student editors at the Crimson can take a walk over to the office of Felix Oberholzer-Gee, who is a professor at Harvard, and has done a nice study debunking almost everything the editors state above. The study shows that as intellectual property laws were ignored to a greater degree, the amount of creation actually increased. This might seem counterintuitive to the staff at the Crimson, but it's really not that complex if you think about how creation and innovation actually works. Most people create and innovate not to get "intellectual property" but because they want to create and get work out there, or because they have a general need to innovate. On top of that, creation and innovation are almost always part of an ongoing process that builds on the works of others. Ray Charles, famously, invented soul music by infringing on copyrights.

The motivation is not "intellectual property." The motivation may be a personal need. It may be money. It may be just a need to create/innovate. But none of that requires intellectual property. In fact, much of it is hindered by intellectual property that puts up toll booths on creation and innovation.

Claiming straight up that there is "no motivation" to create new works without protections is simply wrong and it's sad that a publication like the Harvard Crimson would make such false claims.

Second, at a broader level, intellectual property rights are important because each person has a fundamental right to enjoy the fruits of his or her mental labor. Intellectual entrepreneurship requires a broad societal commitment to the rule of law and the importance of private enterprise.Once again, the staff at the Crimson might benefit by taking a walk from their offices over to folks who actually know what they're talking about. I'm sure the folks at the Berkman Center can help out. US copyright law is not about "a fundamental right to enjoy the fruits of his or her mental labor." That's because no such right exists, fundamental or not. US intellectual property laws are about promoting the progress -- i.e., for the benefit of everyone, not to just allow someone to "enjoy the fruits of his or her mental labor." If the Crimson staff understood copyright law, they would be familiar with the Supreme Court's important ruling in Feist, where it directly rejects the entire idea that there's any "fundamental right" as described by the Crimson editors.

Or better yet, if the Crimson staff were aware of the historical basis of copyright law, they would know that for centuries the idea that you have a right to the fruits of your mental labor has long been rejected. From all the way back in 1791, when this issue was being debated in France, Jean Le Chapelier rejected this very notion, pointing out that it was fine for creators to capture some of the fruit of their labors, but by the very nature of content, the idea that they should capture all of it made little sense:

When an author has delivered his work to the public, when this work is in the hands of everyone, that all educated men know it, that they have seized all beauties it contains, that they have entrusted the happiest lines to their memory; it seems that from this moment, the writer has associated the public with his property, or rather he has transferred it entirely to it...The point isn't that a content creator should not be able to profit from their works, but claiming a "fundamental right" is misleading and wrong on two specific accounts: (1) It implies that any and all "fruit" should go to the content creator. Yet, as we know from basic economics, the natural "spillovers" are actually quite beneficial to society. (2) It suggests that the only way to capture some of that fruit is via protectionism in the form of intellectual property laws. But, as we've been showing for years, there are all sorts of ways to capture revenue from content creation or innovation without relying on intellectual property law. I'm all for content creators "enjoying the fruit" of their labors, but the way you do that is by having a good business model. That's separate from intellectual property.

For a university that has such wonderful economics and law professors, you would think that the staff would seek to understand this issue before putting forth such an editorial based on faulty assumptions.

Filed Under: copyright, harvard crimson, history

Companies: mpaa